When David Taylor, executive chef at Twisted Toque, in London, Ont., was curating the cross-country menu for his new Canadian-themed restaurant last year, he found isolating the cuisine of Ontario to be the biggest challenge, as what we eat in this province is at once a collective of everything and an entity unique unto itself.

Ontario is the amalgam of a multitude of influences, and so it stands to reason that its food would be, too. All of the farmers, greengrocers, butchers, shopkeepers and restaurateurs who have plied their trade here before; all of the immigrants — from the Indigenous through Brits, Scots and Francophones to the more modern sway of Eastern Europeans and Southeast Asians — who have laid claim to the land and tapped its bounty in the creation of their carried-with-them recipes; all of them have left a stamp. And these stamps continue to inform the preparation of the locally produced meats, eggs, dairy products and vegetables into what Liz Driver, director/curator of Toronto’s historic Campbell House, calls “the complicated story” of Ontario cuisine.

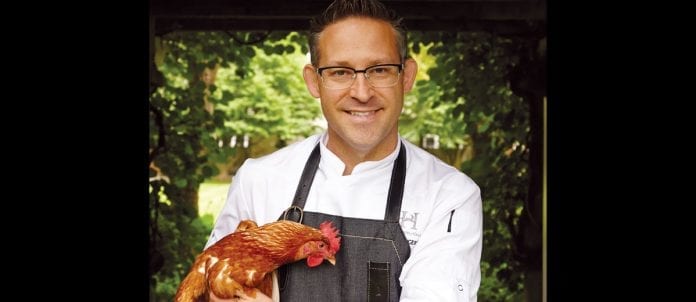

“It’s not about Ontario food; it’s about the food of Ontario,” says Agatha Podgorski, community manager at Culinary Tourism Alliance. “We’re very ingredient-driven here.” That’s because those ingredients flourish here in what chef Brad Long calls “the most intense concentration of Grade-A farmland you could ever dream of — the Garden of Eden.” In his post as owner/chef at Café Belong and Belong Catering in Toronto, he exploits the spoils of that special terroir in dishes such as Roasted Heirloom Roots ($24) and Winter Grain Salad ($16). “We grow great vegetables that, unbeknownst to most Ontarians, are sold elsewhere at a premium,” he says, pointing out that American grocers highlight “Ontario potatoes” and “Holland Marsh carrots,” and sell them for more than their local produce. At Langdon Hall in Cambridge, Ont., executive chef Jason Bangerter distinguishes his restaurant’s cuisine with the morel mushrooms, wild leeks, wild ginger, watercress in the stream, explosive wild-mint bunches and other indigenous produce, along with the naturally spawned salmon, trout, pickerel, pike and bass and yellow-tailed deer, wild turkeys and rabbits that populate the 75 acres of ancient Canadian Carolinian forest on which his relais and chateaux — the only one in Ontario and the province’s only CAA five-diamond restaurant — languishes. Think hay-baked lamb with roasted parsley ruit, pickled-garlic cream and toasted hay jus ($48) and Sweetbreads Forestière with foraged mushrooms, cognac and crispy sourdough ($27).

“This is truly where Ontario cuisine comes from,” Bangerter says.

LAY OF THE LAND

The legacy of appreciation for Ontario’s natural fertility dates back to the start. The Algonquin, Iroquois and Ojibway called the triumvirate of their diet — squash, corn (or maize) and beans — “the three sisters.” Meat was less common in the country’s early days and whatever was eaten was generally in a boiled state (only the wealthy could afford a spit), right up to the early 1900s (when factory farming, preservation and widespread refrigeration changed the scene). That explains why colonial cookbooks focus on soups and stews. And because the majority of families couldn’t afford a lot of meat, bread took the lead on injecting a note of heartiness to the meals.

That may be why small towns in Ontario launched themselves into existence courtesy of centrepiece mills. That the province could successfully grow five classes of wheat so bountifully inside of a single growing area, says Mark Hayhoe, is a genuinely noteworthy distinction. His family was the sixth owner of a mill on the Humber xRiver, which was built in present-day Woodbridge, Ont., in 1828. The variety means there’s no shortage of wheat for making bread and pasta, but also an abundance of soft wheats good for making cookies, cakes and pancakes.

With regard to pancakes, the new land’s natural surfeit of maple syrup surfaced early as another Ontario staple. Indeed, in the settlement’s youngest days, this tree-tapped sweetness was the “poor man’s sugar.” Now we have the absolute reverse, points out Driver, with maple syrup occupying revered and expensive pedestals while white sugar gets commodity billing.

CULTURAL REFRESH

The immigrant experience surfaces as the second serious pillar of Ontario’s food domicile. The convention of people hitting our shores with fully formed culinary traditions that find new life through the bounty Ontario farms gift them is a longstanding one. For hundreds of years, says Long, newcomers have arrived in this province armed with expectations for how the ingredients in their dishes would grow based on their experience. When they found the “heaven” that is Ontario’s farmland, he says, they were blown away and their recipes were transformed into something new. “It’s been almost like hitting a refresh button on their culture.”

The fact that Ontario’s population is highly developed and conducive to information dissemination pushes the immigrant cuisine piece even more. And the professional-training side of the equation does its part, too. “Ontario’s culinary schools are stepping up their game,” Podgorski says. “When you go to culinary school in France, you end up with classic French cooking techniques. But when you go to culinary school here, the education is so varied. People come from all over the world and prepare food they’ve been preparing all of their lives. What makes it the food of Ontario is that they’re making it here.” More than that, though, it’s the people they find themselves making it alongside. Ontarians are unique in the expansive reception they’re prepared to extend to novel, unfamiliar recipes. Indeed, says Ryan Whibbs, a professor at George Brown College’s chef school who just completed a PhD. in food history, people of this province have been cultivating a genuine curiosity about the food of others since the 1950s. Unlike those cultures that will only embrace outsiders’ cuisine if it amalgamates with its own. Ontarians have proven themselves highly receptive to the adoption of new ideas. “Other places, even within Canada, simply don’t have that openness,” he says.

“We’re through our days of British imperial cooking — our roasts, dumplings and stews — and are willing to explore new tastes,” Whibbs says. He calls those runny-with-custard Portuguese tarts you can buy throughout Toronto a benchmark on how Ontarians approach immigrants’ cuisine “From an expectation that we’ll meet people from different places here comes an expectation that we’ll show each other how to do things. Looking to other cultures for culinary expertise is the defining aspect of Ontario.”

FOOD FOR ALL SEASONS

Ontario’s cuisine is most assuredly the product of its seasons. “It took me a really long time to realize how unique seasons are,” Podgorski says. “Most of the world’s population doesn’t experience seasons. They don’t have four months of the year where everything is buried in snow and another four months where it’s a glut. It’s a unique thing that Canada and people in our hemisphere experience that shapes the food culture.”

While everything’s available all of the time in Ontario thanks to imports, there’s a special reverence reserved for food that’s grown here. In June and July, the appearance of Ontario’s juicy strawberries is cause for genuine excitement. Even wild leeks — in their prime for only two weeks — have the culty-est of followings. HOMEGROWN HEROS Less directly dependent on the growing season are the various prepared dishes engaged foodies consider the most quintessential of Ontario cuisine. Topping that list without hesitation? Butter tarts. “Sometimes recipes get introduced by chefs at grand hotels, but I truly believe the butter tart sprang out of the grassroots Ontario kitchens in the beginning of the 20th century,” says Driver. That they’ve been ubiquitous ever since, she believes, is because the ingredients are in everyone’s pantry — and were available in 1901 when the earliest butter tart recipe made an appearance in a cookbook out of Barrie, Ont. That the humble butter tart enjoys the reputation it does, says Hayhoe, is a reflection of the soft wheat that grows in such abundance here. Desserts, he says, are a rich arena for Ontario food activity because of that wheat, which is low in protein, high in starch and excellent for cakes, pastries and pies.

More than that, says Driver, Ontario cuisine sings for its dishes that draw on the province’s connection to the land. “A brook trout fried in butter in an iron pan on a cookstove, or a blueberry pie made with wild berries that you picked — these things are fresh, they’re seasonal and they’re so Ontario.

“But underline butter tarts,” urges Podgorski on a final consideration of Ontario cuisine. “We’re obsessed.”

Volume 50, Number 1

Written By Laura Pratt