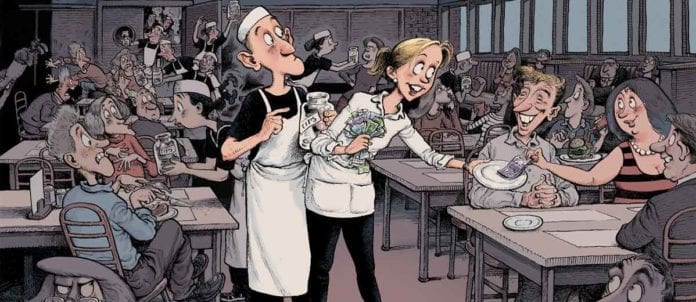

In a world that’s gone mad for celebrity chefs and the latest food trends, diners are forcing restaurants to seek out ever-more top-notch staff. Meanwhile, “many people don’t look at the foodservice industry as a career,” says Jeff Dover, vice-president of Toronto-based foodservice consulting firm fsStrategy. “We’re not doing a good job of making it a career option and something that people are proud to do.”

Foodservice businesses are facing the threat of increasing labour shortages, says Tony Elenis, president and CEO of the Mississauga-based Ontario Restaurant Hotel & Motel Association (ORHMA). “The Baby Boomers are leaving every year and we have difficulty filling those voids.”

Engaging the upcoming millennial cohort isn’t difficult; simple appreciation can go a long way. “Companies successful in retaining millennial employees are good at providing constant feedback,” notes Dover. “This is a generation that grew up with instant gratification. They want to be appreciated for doing a good job.”

To this end, “we’ve always been pretty progressive with the way we view our employees,” says Phil Wylie, VP of People for Toronto-based Oliver & Bonacini Restaurants. “We were one of the first groups to get rid of day rates. All of our managers get benefits.” There are also family-dining discounts and popular contests. “It’s those little things,” he says. “It’s a tough job and you have to find ways to keep [staff] inspired.”

Rodney’s Oyster House in Toronto has kept some workers for 20 years. “It’s stable; it’s consistent, so it’s somewhere people can build their lives around,” says owner and front-of-house manager Bronwen Clark. “We have full dental plans for our front-of-house staff who have been here more than two years.”One challenge in retaining good employees is scheduling, says Dover. “Everyone works nights and weekends, but if something is important — a wedding, a concert — you try and work around people’s schedules and let it be known that you’ll work around them.”

“Ten years ago, servers were happy to work weekends and holidays,” says Andrew Laffey, co-owner of The Hot House in Toronto with his wife Elinor Laffey. Their popular downtown location can “offer flexibility where most in the industry would not be able to; you can work full-time, part-time, lunch or weekends.”

But not everyone has this luxury, says Elenis, and “scheduling is a fundamental employer need in the industry.”

ORHMA is currently participating in the Ontario government’s review of its labour standards to represent the realistic needs and concerns of foodservice employers. In a statement released in May, Elenis cautioned against layering labour reforms and potential wage increases on top of growing government policies that impact the hospitality sector, such as rising hydro costs, Canada Pension Plan enhancements, cap and trade and rising municipal property taxes.

“The Premier wants to protect vulnerable workers — Ontario’s hospitality employers, including small-business operators, are the vulnerable ones,” he says. “They are the people expected to pay for the suggested changes to labour laws.”

He adds that “Immigration laws are not conducive to employment in our industry; [Canada’s Temporary Foreign Workers program] is something that needs to be looked at, because we need unskilled people as well as skilled people in our industry. There are restrictions on how many people you can bring in, based on unemployment in your area, but there are hotels in [remote] resort areas like Muskoka, where no one shows up to interviews and the conclusion is that no one wants to work in the industry.”

Front-of-House versus Kitchen

“We have a bigger challenge keeping people in the kitchen than in service,” says Wylie. With tip levels rising above 15 per cent, “the server job is turning into a lifetime career. Unfortunately, the wages in the back are not as competitive, so we have been increasing our tip-out in all of our restaurants so more of the gratuity goes to the guys in the back. They wouldn’t be able to serve if there wasn’t great food coming out from the back.”

Tip pools or “tip-out” arrangements are a common strategy to address this inequity and a few companies are testing a no-tipping policy. In 2016, Ontario made it illegal for an employer to use their employees’ tips to cover losses or damages, but may still redistribute them through a pool. Newfoundland has a similar policy, while Prince Edward Island requires employers to advise an employee in writing at the time of hiring if a tip-out policy is in effect. Quebec requires workers to report their tips to their employer, who, in turn, must report them to government, and tips can be pooled.

A tip-out is “very good solution,” says Elenis. “These individuals who work in the service industry are entitled to it, and it’s up to employers to determine the mix that will go to the kitchen and support staff.”

At Oliver & Bonacini, “we spend a lot of time with our cooks,” Wylie says. Career development and training are discussed regularly. With “multiple brands with different kinds of food,” the company can offer a range of experience within the single brand. “We’ve had so many people work at O&B who then go off and open their own restaurants and we’re proud of that.”

At The Hot House, “the servers will tip out their colleagues, like busboys and bar staff, but the back-of-house do not [benefit from] tip sharing,” says Laffey, who does not dictate how the pool will be distributed.

At the Toronto location of Rodney’s Oyster House, “we don’t do any of the house tip-outs that a lot of restaurants do. We have managers who work on the floor, but they don’t get tipped out,” says Clark. The company’s two-year-old Calgary outlet is “totally different; we pool our gratuities, so everybody has to work in teams.”

Ultimately, she says, “a restaurant is not the most profitable business you can get into, but it’s a lifestyle, a community, a culture of people. You’re not making 50-per-cent profit at the end of the month, but that’s okay, because you have this whole family of people here.”

Wage Wars

Across North America, many city, state and provincial governments are planning substantial increases in minimum wage, partly due to a “Fight for $15” campaign by U.S. labour interests. In 2016, Alberta eliminated separate wage levels for liquor servers and raised minimum wage to $12.20 per hour, with increases set for 2017 ($13.60) and 2018 ($15). In 2014, Ontario raised its minimum wage to $11, with increases based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). As of October 2017, it stands at $11.60 ($10.90 for students and $10.10 for liquor servers), but the province plans to introduce increases to $14 in 2018 and $15 in 2019,while it broadens workers’ access to benefits such as as paid sick days, vacation and leave. (Some B.C. politicians have likewise been eyeing a $15 minimum.)

Ontario has not yet announced how much tipped workers will be paid. This issue has been controversial in locations such as Minneapolis and Maine (which flip-flopped on its original plan to eliminate a lower rate for tipped workers after protest by restaurant owners and workers.)

ORHMA has been outspoken in its criticism of the speed with which Ontario is moving forward with increases. “There is something seriously wrong in Ontario when hardworking business owners and operators are punished for providing jobs,” Elenis said in a statement earlier this year. “We are an industry that is an entry-level employer for many youth, seniors, immigrants and non-skilled workers. The Premier clearly has not considered the sustainment of our economic model with rigid price-point limitations in a highly competitive environment. Ontario’s restaurants have the lowest profit margins in all of Canada.”

Elenis expresses particular concern for smaller businesses, as well as for consumers: since 2014, Ontario had planned that “minimum wage would go up every October and then be reviewed again,” he says. “All of a sudden, you have something that does not give enough time for the industry to plan.”

In comparison, “California took five years [to 2022], in a state that has better profitability in this industry than Ontario, to increase to $15 for employers of 25 or less, and four years for 26 or more,” says Elenis. The cities of San Francisco and San Jose are moving faster, with plans to reach $15 in 2018 and 2019, respectively. In Seattle, Portland employers are already expected to pay $15; others will have until 2021. “At least it gives time for restaurant owners to say ‘I’m going to sell it,’ or raise prices.”

“It’s a big jump,” says Dover. “When you look at the average restaurant net profit at about four per cent, I’m not sure they’re going to be able to pass the price increase off as fast as the minimum wage is going up.”Another implication of an increased minimum wage is the associated increase in payroll taxes — “when payroll goes up, CPP goes up, employment insurance goes up, Workers Compensation contributions go up and our industry employers absorb those costs as well,” says Elenis.

“It’s something we’re still planning on how we’re going to deal with,” says Wylie. “We’re going to have to raise prices to some degree. There’s a domino effect: people who were already getting $15 will want more and it will affect our food costs” [since suppliers will be paying their workers more].

“You have to increase your prices on food,” says Clark, who has already felt the impact of a higher minimum wage in her Calgary location. However, the clientele in her moderately upscale establishment “generally didn’t notice,” she says. Since margins on seafood are so narrow, Rodney’s passed on the increase in its alcohol prices. “It’s not enormous,” she says. “You’re not increasing by $10; you’re increasing the price of the beer by about 50 cents.”

So far, the evidence about the likely impact of minimum-wage increases on businesses, workers and the general economy is scarce, and even contradictory. “Classical economics suggests there’s going to be huge job losses [yet] studies indicate that’s not likely to be the case,” Bernie Wolf, economics professor at York University’s Schulich School of Business, told CBC News in an interview last June.

The Effects of a $15 Minimum Wage in New York State (March 2016) suggested that “the costs of the minimum wage will be borne by turnover reductions, productivity increases and modest price increases,” while an April 2017 study of the restaurant industry in San Francisco, Survival of the Fittest, estimated that “a one-dollar increase in the minimum wage leads to a 14-per-cent increase in the likelihood of [closure] for a 3.5-star restaurant, with most risk for “lower quality restaurants, which are already closer to the margin of exit” and “no discernible impact for a 5-star restaurant.”

Volume 50, Number 5

Written by Sarah B. Hood