There were those who said it would never last three years, let alone three decades. But, in hindsight, it’s now apparent April 4, 1983, was the best time The Cookbook Store could have opened.

Just a year before opening in Toronto, in the autumn of 1982, the publication of several books changed the world of cookbooks and cooking forever. At the top of the scale, Glorious Food and Martha Stewart’s Entertaining ushered in the era of the “coffee-table” book. Although the recipes within it were not necessarily complicated, the heavy paper and masses of gorgeous colour photographs gave the average reader access to a world of wealth. Soho Charcuterie and The Silver Palate Cookbook, based on a New York restaurant and Upper West Side food, respectively, were not as elegant but equally as influential. The latter, from Workman Publishing, with its colourful sidebars, became the blueprint for cookbooks for years to come while its recipe for Chicken Marbella still graces buffet tables 30 years later. Collectively, these cookbooks convinced home cooks they could be their own caterers.

Stepping back, in the ’70s, haute-cuisine restaurants embraced French cooking. Then dubbed nouvelle cuisine, chefs dropped the heavy cream sauces and let the essence of the main ingredient shine. Likewise, plate presentation was pared down to enhance rather than mask the look of a dish. But, as a new decade dawned, some cooks faltered. In less practiced hands, nouvelle cuisine devolved into a practice where a chef threw a strawberry and a slice of kiwi on whatever was being served — fish, roast beef, lamb — and called it a masterpiece.

Looking back, the seemingly lackadaisical cooking makes sense. At the time, there was a disconnect between the books that chefs were using and the dishes they wanted to create. The Escoffier Cookbook, Wenzel’s Menu Maker, The New International Confectioner, Le Repertoire de la Cuisine and Herings Dictionary were the tomes on which a chef built his career. Their weightiness was symbolic of the heavy cuisine codified within. Books were authored by pioneers of the new wave of French cooking, including Paul Bocuse, the Troisgros brothers and Alain Senderens. The chefs shared their recipes but not necessarily their philosophy, and, there weren’t many colour photos to guide the reader.

That is in sharp contrast to the contemporary equivalent. When perusing books written by today’s chefs — Thomas Keller, René Redzepi, FerranAdria, AndoniAduri and Magnus Nilsson — cooking philosophies and photographs are front and centre while the recipes almost seem an afterthought. Such books are proof of today’s chef personalities, which are aided and abetted by the proliferation of cooking shows and the rise of social media. In the 1980s, such an online power was unimaginable.

Look at that list of names of today’s aforementioned culinary stars, and you notice another change. The chefs are American, Spanish, Scandinavian, while the French influence has all but disappeared. Instead, the Spaniards, masters of molecular gastronomy, have become the chefs most likely to be copied, with the Scandinavians, and their acute sense of place, not far behind.

That sense of place, now so important, follows the rise of fusion food. Hugh Carpenter’s 1993 cookbook, Pacific Flavors, was one of the first books to marry Southeast Asian ingredients with western techniques. Like nouvelle cuisine, what began as a great idea degenerated into a sometimes horrible cacophony of flavours on the plate — think Italian, Mexican and Asian ingredients competing for attention. But, the trend did introduce some positive ideas to the industry. It brought the Australians and their restrained approach to fusion cooking to the attention of North American cooks and diners. Twenty years later, the worst examples of fusion cooking have been replaced with more judicious approaches that weigh the reality of place with the appropriateness of international ingredients.

These days, environmental considerations are also influencing how chefs interpret fusion cooking. For example, in the recently published Smoke and Pickles, Brooklyn-born Korean American, Edward Lee, blends the flavours and techniques used by his Korean family to bring a new zip to the most insular of American regional cuisine. With pickling and smoking common to both cultures, his version of fusion makes perfect sense. Moreover, Fergus Henderson of St. John in London has brought nose-to-tail eating to a new generation of meat enthusiasts, encouraging chefs to use the whole beast. All of this reduces kitchen waste, creating a more efficient, sustainable and profitable kitchen.

Echoes of past trends continue to reverberate. Flip through the recent Sat Bains’ Too Many Chiefs Only One Indian to see how the great play between texture and colour in the best of nouvelle cuisine has translated to the techniques of the 21st century. It’s just a matter of time before the architectural plate returns. The late, great Jean-Louis Palladin, of the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C., was a master of this form. Memorialized in Jean-Louis: Cooking with the Seasons, such art was best expressed by a breathtaking black-and-white block of potato slices layered with black truffles.

Overall, it’s clear there’s much irony in the modern culinary world. While chefs are interested in locavore cooking, they also search for inspiration from afar by seeking stage positions, particularly in Denmark, Spain and Australia. In the name of molecular gastronomy, they use food additives, which wouldn’t be accepted in packages from big suppliers. Yet, ingredients with a pedigree are also important — think heirloom vegetables and meat from pastured heritage animal breeds. Perhaps these examples, which seem to represent contradictions, prove that in today’s modern culinary world, we can have it all.

Today, an increased number of home kitchens have professional equipment such as multi-burner stoves, sub-zero refrigerators and immersion circulators. Restaurant menus often mirror what the customer would formerly have cooked at home — with vegetarian, vegan, raw food and gluten-free selections now taking centre plate. So, 30 years after The Cookbook Store opened, the blurring of lines between home and professional kitchens that was prevalent in the spring of 1983 has now come full circle. l

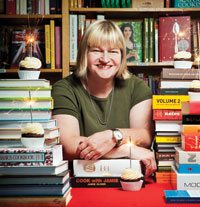

Alison Fryer has been the manager of The Cookbook Store since its inception in 1983 and is a frequent media source for her expertise in cooking and cookbooks. Jennifer Grange, assistant manager at The Cookbook Store, has a background in journalism and cooking, and has been working at the store since July 1983. For more details, visit cook-book.com.