Collard greens, the southern soul-food staple, are taking the spotlight across North America. Chicago-based research firm Technomic’s “2015 10 Trends to Watch” report, lists collard greens (and cauliflower) as “next-gen cruciferous veggies” to watch. Hugh Acheson, a Canadian-born chef and owner of multiple restaurants, who now calls Georgia his home, declared collards “the new kale” during an appearance on Top Chef. The dark-hued loose-leafed greens are part of the Brassica oleracea L. (Acephala group) family, the same cultivar group as kale, cabbage, broccoli and spring greens. Originally dubbed colewort (or wild cabbage plant), the veg likely originated in and around eastern Europe or Asia Minor and grows in cooler, temperate zones, sprouting leaves arranged in a rosette-like pattern around a stocky main stem. The leafy green is used in soups, sautéed — often with a savoury hit of pork — wilted, fried or even pickled. And, it’s more than a culinary standby in the American south. In Portugal, it’s used in caldo verde soup, and Brazilians favour it in bean-based stews called feijoada.

Collard greens, the southern soul-food staple, are taking the spotlight across North America. Chicago-based research firm Technomic’s “2015 10 Trends to Watch” report, lists collard greens (and cauliflower) as “next-gen cruciferous veggies” to watch. Hugh Acheson, a Canadian-born chef and owner of multiple restaurants, who now calls Georgia his home, declared collards “the new kale” during an appearance on Top Chef. The dark-hued loose-leafed greens are part of the Brassica oleracea L. (Acephala group) family, the same cultivar group as kale, cabbage, broccoli and spring greens. Originally dubbed colewort (or wild cabbage plant), the veg likely originated in and around eastern Europe or Asia Minor and grows in cooler, temperate zones, sprouting leaves arranged in a rosette-like pattern around a stocky main stem. The leafy green is used in soups, sautéed — often with a savoury hit of pork — wilted, fried or even pickled. And, it’s more than a culinary standby in the American south. In Portugal, it’s used in caldo verde soup, and Brazilians favour it in bean-based stews called feijoada.

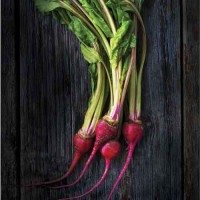

Beets are among the healthiest foods to eat. A few years ago that might have been their downfall. But, today, as consumers hunger for healthier foods, and new varieties of beets are now available, the root vegetable has become a menu staple and a chef favourite. Forming part of the Amarathaceae family, which also includes vegetables such as Swiss Chard, the scientific name for beets is Beta Vulgaris. While once known as the main ingredient in borscht soup, today’s chefs are presenting beets as the star ingredient in salads, either accompanied by goat’s cheese or simply roasted with a sprinkle of extra virgin olive oil and lemon juice. And, at only 45 calories per 100 g, the once lowly beet is also one of the most versatile vegetables and is also ideal for juicing. Typically red to purple in colour, beets are now available in other colours, including orange-yellow and even white. In fact, one of the most popular varieties on restaurant menus is the chioggia beet, also known as the candy-cane beet. Its white and pink stripes create an interesting visual that allows chefs to get creative on the plate.

Beets are among the healthiest foods to eat. A few years ago that might have been their downfall. But, today, as consumers hunger for healthier foods, and new varieties of beets are now available, the root vegetable has become a menu staple and a chef favourite. Forming part of the Amarathaceae family, which also includes vegetables such as Swiss Chard, the scientific name for beets is Beta Vulgaris. While once known as the main ingredient in borscht soup, today’s chefs are presenting beets as the star ingredient in salads, either accompanied by goat’s cheese or simply roasted with a sprinkle of extra virgin olive oil and lemon juice. And, at only 45 calories per 100 g, the once lowly beet is also one of the most versatile vegetables and is also ideal for juicing. Typically red to purple in colour, beets are now available in other colours, including orange-yellow and even white. In fact, one of the most popular varieties on restaurant menus is the chioggia beet, also known as the candy-cane beet. Its white and pink stripes create an interesting visual that allows chefs to get creative on the plate.

A staple in Asian and Caribbean cooking, sea vegetables are one of nature’s original superfoods. The nutritionally dense greens pack a wallop of vitamins and minerals, from calcium, iodine and iron to protein and vitamins A, B, C and E. Anyone who’s had sushi has likely consumed nori, and anyone who’s had seaweed salad has likely enjoyed arame. Other sea veggies include dulse, kombu, kelp and wakame. And, agar agar is a thickening agent of choice for vegetarians, which manufacturers also use in everything from salad dressings to toothpaste. Justin Cournoyer, chef/owner of Toronto’s Actinolite Restaurant, uses fresh or dried sea vegetables, depending on the season. He sources the “Canadian gems” from the East Coast. “Making use of these healthy and delicious items that grow in abundance where we live, instead of shipping ingredients grown in hotter climates that are not sustainable in Canada, [is key],” says Cournoyer, who relishes the umami that the veggies impart. Used to flavour broths, noodles or stews, consumed fresh or dried, Cournoyer pairs them with vegetables such as cucumber, asparagus and dark, leafy greens.

Laying hens have been a part of Canadian husbandry since the days of Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain. By the late 1800s the poultry industry was working to improve hen production and searching for the tastiest egg. We simply have a history of loving eggs. But between 1980 and 1995, Canadians’ annual egg consumption dropped from 22 dozen per person to 17 dozen, according to Ottawa-based Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. The culprit? Cholesterol. Health concerns eased when the “omega-3” egg appeared, but any egg has high amounts of protein, vitamin B12 and other nutrients, which are essential for maintaining good health, says Jane Dummer, registered dietitian. “Most research and health experts suggest eating one egg a day is fine,” she adds. “However, if you have a history of heart disease or Type 2 diabetes, it is best to consult your dietitian.” In their restaurant application, eggs are both ingredient and dish, and, with the rising cost of meats, they are a relatively inexpensive protein. The popularity of dishes such as the fabulous Korean bibimbap and spicy huevos rancheros feature eggs as a centre-of-the-plate protein and can turn a classic brunch eggs Benedict into a nifty slider-like dinner app.

Laying hens have been a part of Canadian husbandry since the days of Jacques Cartier and Samuel de Champlain. By the late 1800s the poultry industry was working to improve hen production and searching for the tastiest egg. We simply have a history of loving eggs. But between 1980 and 1995, Canadians’ annual egg consumption dropped from 22 dozen per person to 17 dozen, according to Ottawa-based Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. The culprit? Cholesterol. Health concerns eased when the “omega-3” egg appeared, but any egg has high amounts of protein, vitamin B12 and other nutrients, which are essential for maintaining good health, says Jane Dummer, registered dietitian. “Most research and health experts suggest eating one egg a day is fine,” she adds. “However, if you have a history of heart disease or Type 2 diabetes, it is best to consult your dietitian.” In their restaurant application, eggs are both ingredient and dish, and, with the rising cost of meats, they are a relatively inexpensive protein. The popularity of dishes such as the fabulous Korean bibimbap and spicy huevos rancheros feature eggs as a centre-of-the-plate protein and can turn a classic brunch eggs Benedict into a nifty slider-like dinner app.

Whether it’s sturgeon, geoduck clams or massive Humboldt squid, chefs are discovering odd and even ugly fish can be extremely tasty. “Our objective is to utilize lesser-known ingredients while introducing guests to new experiences and flavours,” says Frank Pabst, executive chef of Vancouver’s Blue Water Café, who celebrates unique, sustainable seafood at his annual Unsung Heroes dinner, which features dishes such as stir-fried jellyfish and poached periwinkles. While many popular species are unsustainable choices, many of these unusual fish remain plentiful in the wild, though still rare on menus. Herring and mackerel, for example, are often still sold for bait, while sturgeon, though endangered in the wild, is now being sustainably farmed for caviar and meat. “Sturgeon have many uses — the liver is like foie, the skin is like pork, and though there are no bones, there’s marrow,” says chef Jefferson Alvarez who uses the certified-organic white sturgeon meat produced by Northern Divine at its land-based farm in B.C. on his $150, 10-course tasting menu at Vancouver’s Secret Location. He cures the meat “like candied salmon,” boils, dries and then fries the skin “like chicharron,” sears the liver and adds the gelatinous marrow to soup. Other chefs are discovering new ways to serve Pacific squid. At Wolf in the Fog, chef Nick Nutting serves a one-inch thick piece of local Humboldt squid, charred for 45 seconds in smoking grapeseed oil, then thinly sliced and offered alongside a Vietnamese-style slaw of carrot, cucumber and daikon radish. “I want to showcase the awesome seafood that’s found in Tofino and elevate it,” says Nutting.

Whether it’s sturgeon, geoduck clams or massive Humboldt squid, chefs are discovering odd and even ugly fish can be extremely tasty. “Our objective is to utilize lesser-known ingredients while introducing guests to new experiences and flavours,” says Frank Pabst, executive chef of Vancouver’s Blue Water Café, who celebrates unique, sustainable seafood at his annual Unsung Heroes dinner, which features dishes such as stir-fried jellyfish and poached periwinkles. While many popular species are unsustainable choices, many of these unusual fish remain plentiful in the wild, though still rare on menus. Herring and mackerel, for example, are often still sold for bait, while sturgeon, though endangered in the wild, is now being sustainably farmed for caviar and meat. “Sturgeon have many uses — the liver is like foie, the skin is like pork, and though there are no bones, there’s marrow,” says chef Jefferson Alvarez who uses the certified-organic white sturgeon meat produced by Northern Divine at its land-based farm in B.C. on his $150, 10-course tasting menu at Vancouver’s Secret Location. He cures the meat “like candied salmon,” boils, dries and then fries the skin “like chicharron,” sears the liver and adds the gelatinous marrow to soup. Other chefs are discovering new ways to serve Pacific squid. At Wolf in the Fog, chef Nick Nutting serves a one-inch thick piece of local Humboldt squid, charred for 45 seconds in smoking grapeseed oil, then thinly sliced and offered alongside a Vietnamese-style slaw of carrot, cucumber and daikon radish. “I want to showcase the awesome seafood that’s found in Tofino and elevate it,” says Nutting.

It’s been a decade since the Vancouver Aquarium launched its Ocean Wise program and began helping chefs identify the best choices for sustainable seafood. Now, an increasing number of toques are offering seafood such as rare spot prawns and giant Pacific octopus on their menus, developing creative ways to serve Canada’s cleanest catches. “One of our proudest moments is hearing consumers ask for Ocean Wise options in restaurants and markets to ensure the seafood they are eating is sustainably sourced,” says Dolf DeJong, VP, Conservation and Education, Vancouver Aquarium. Spot prawns, one of the few ocean-friendly shrimp available, are now celebrated with festivals and special menus during the short spring fishing season. Chef Chris Whittaker of Vancouver’s Forage restaurant helped organize the first spot prawn festivals in Vancouver and now features the sweet, crisp shrimp on his menu. Sadly, the large prawn only accounts for one per cent of the shrimp landed, and the highly perishable delicacy is only available fresh for a few weeks in May. Meanwhile, the giant Pacific octopus, the world’s largest, is an Ocean Wise choice when diver-caught in B.C. but not when caught as bycatch from destructive bottom-trawling. Octopus feed on crabs and prawns, so they’re often pulled up in the traps used to catch those shellfish.

It’s been a decade since the Vancouver Aquarium launched its Ocean Wise program and began helping chefs identify the best choices for sustainable seafood. Now, an increasing number of toques are offering seafood such as rare spot prawns and giant Pacific octopus on their menus, developing creative ways to serve Canada’s cleanest catches. “One of our proudest moments is hearing consumers ask for Ocean Wise options in restaurants and markets to ensure the seafood they are eating is sustainably sourced,” says Dolf DeJong, VP, Conservation and Education, Vancouver Aquarium. Spot prawns, one of the few ocean-friendly shrimp available, are now celebrated with festivals and special menus during the short spring fishing season. Chef Chris Whittaker of Vancouver’s Forage restaurant helped organize the first spot prawn festivals in Vancouver and now features the sweet, crisp shrimp on his menu. Sadly, the large prawn only accounts for one per cent of the shrimp landed, and the highly perishable delicacy is only available fresh for a few weeks in May. Meanwhile, the giant Pacific octopus, the world’s largest, is an Ocean Wise choice when diver-caught in B.C. but not when caught as bycatch from destructive bottom-trawling. Octopus feed on crabs and prawns, so they’re often pulled up in the traps used to catch those shellfish.

Cauliflower — like its cousins the collard greens, broccoli, kale and watercress — is part of the cabbage or the Brassica oleracea family and dates back to 6th century BC. Chefs, such as Dave Mottershall, owner of Toronto’s Loka Snacks, appreciate the vegetable’s versatility. It can be eaten raw, baked, fried, pickled, steamed, braised, boiled or grilled, has the texture of starch (although it’s not very starchy) and often replaces flour, rice or potatoes in dishes. It’s also a toothsome vegetable, which means it’s a culinary body double for proteins when thickly sliced, like a steak, as it holds its shape during cooking and caramelizes when baked or grilled. Low-carb, low-fat and high in fibre and vitamin C, it’s a healthy option winning attention on vegetarian, vegan and meaty menus across the country.

Cauliflower — like its cousins the collard greens, broccoli, kale and watercress — is part of the cabbage or the Brassica oleracea family and dates back to 6th century BC. Chefs, such as Dave Mottershall, owner of Toronto’s Loka Snacks, appreciate the vegetable’s versatility. It can be eaten raw, baked, fried, pickled, steamed, braised, boiled or grilled, has the texture of starch (although it’s not very starchy) and often replaces flour, rice or potatoes in dishes. It’s also a toothsome vegetable, which means it’s a culinary body double for proteins when thickly sliced, like a steak, as it holds its shape during cooking and caramelizes when baked or grilled. Low-carb, low-fat and high in fibre and vitamin C, it’s a healthy option winning attention on vegetarian, vegan and meaty menus across the country.

The cliché is The Flintstones cartoon and “brontosaurus ribs” toppling Fred’s car at the Palaeolithic drive-thru. Depending on the cut, it’s not far off the mark since beef ribs can be stone-age large — there are 13 ribs on beef cattle. The first four are in the shoulder (chuck) and can be butchered as longer English-cut ribs and “flanken-style” cut across the ribs, according to Dave Meli, head butcher at Toronto’s The Healthy Butcher. The fifth to 12th ribs give us full back ribs — those long ribs attached to the cattle’s spine — and what you get in rib roast. “Back ribs are the curved, caveman-like beef ribs at barbecue joints, which are braised and grilled with lots of barbecue sauce,” Meli says. However, that’s premium meat, so it can be costly. The key to good beef ribs is the meat-to-fat-to-bone ratio. The muscle itself isn’t necessarily tough, but all of the meat is connected to bone with elastin (which doesn’t break down with cooking) and contains collagen (which does). “That’s why ribs require a decent amount of cooking time, depending on how thick you cut them,” says Meli. And, it’s why they taste so good when prepared properly.

The cliché is The Flintstones cartoon and “brontosaurus ribs” toppling Fred’s car at the Palaeolithic drive-thru. Depending on the cut, it’s not far off the mark since beef ribs can be stone-age large — there are 13 ribs on beef cattle. The first four are in the shoulder (chuck) and can be butchered as longer English-cut ribs and “flanken-style” cut across the ribs, according to Dave Meli, head butcher at Toronto’s The Healthy Butcher. The fifth to 12th ribs give us full back ribs — those long ribs attached to the cattle’s spine — and what you get in rib roast. “Back ribs are the curved, caveman-like beef ribs at barbecue joints, which are braised and grilled with lots of barbecue sauce,” Meli says. However, that’s premium meat, so it can be costly. The key to good beef ribs is the meat-to-fat-to-bone ratio. The muscle itself isn’t necessarily tough, but all of the meat is connected to bone with elastin (which doesn’t break down with cooking) and contains collagen (which does). “That’s why ribs require a decent amount of cooking time, depending on how thick you cut them,” says Meli. And, it’s why they taste so good when prepared properly.